The Future of Money-Like Things

Look at the infrastructure that makes money move to understand the future of monetary forms like Bitcoin

While we rarely think of it in this way, the payment system we use every day is among the most widespread and functional examples of an Internet of Things. It is an array of objects embedded with chips, magnetic stripes, scanners, and touchpads. These things are coordinated through networking protocols used to move information and, ultimately, monetary value.

In payment systems, as flights of imagination get grounded in real infrastructures, interoperability has gone hand in hand with technological inertia. Payment systems have to work, and they have to work everywhere. When you swipe your credit card, it works. No matter where you are in the U.S., if you have money or credit in physical or electronic form, you can pay for stuff.

The payments industry that develops and markets these systems is big business. But it is difficult to measure, since it is made up of so many different kinds of companies: companies that manufacture the plastic cards that turn into credit cards, companies that build all kinds of card readers, database companies that sit behind the major card networks, specialized banks that sit behind payment service providers; and so on. Outside of the industry, people don’t tend to notice payment systems. Like all infrastructure, they think about payment systems only when they don’t work well, when a card is declined or someone starts writing a check at the front of the line at the grocery store. But every time we try to pay for something, small bits of value get transferred between actors in this network, invisibly.

Although it works pretty well most of the time, the payment system is far from uniform. It undermines any notion of linear technological progress. Payment technologies that were invented in the 1960s, like the credit card magnetic stripe, or the 1860s, like uniformly valued, nationally-based paper currency, exist alongside technologies that haven’t been fully invented yet, like Coin, an as-yet unreleased product that permits you to store payment information from multiple cards on one device. During the same day, you might have your card carbon-copied with a zip zap machine, hear modem noises coming from an ATM when you withdraw cash, use a smartphone app to pay for coffee, and be offered the opportunity to pay for a manicure in Bitcoin.

The payment industry does a surprisingly good job at creating interoperability between these varied and uneven systems, but sometimes things go awry. Here’s an example. Earlier this year, Bill (who directs two research centers that deal with money and technology) flew from California (birthplace of the credit card!) to Amsterdam (birthplace of the modern financial bubble!) to attend a conference (on the future of money!) and immediately encountered a consequence of our uneven present money infrastructure. Despite all his bonafides, Bill’s actual practice of money and technology in everyday life makes him highly vulnerable to fraud. He used his debit card to withdraw euros from the airport lobby ATM, and the card was skimmed and cloned. Over the next couple of days, someone, not Bill, had a great time in Amsterdam on his dime.

In Europe, payment cards have included a microchip that prevents this kind of fraud for as long as two decades. Each time a card is inserted into a reader and the correct PIN is entered, the chip uses electricity from the terminal to generate a dynamic authorization code. The United States payment industry, however, has been slow to adopt this technology, continuing to rely on the magnetic stripe that was introduced in the late 1960s. The typical American credit card is notorious for being one of the most hackable payment technologies around. You don’t even need software to do it: just write down all the information printed on the card. Because he is an American and carries the standard American payment card, Bill was the perfect target for traps laid in the ATM of an international airport.

Americans don’t have chip and PIN cards is because of infrastructural inertia. When banks and interbank networks first introduced magnetic stripe payment cards, they also absorbed the cost of outfitting merchants with card readers. Later, independent companies offered merchants point-of-sale devices that also provided additional services like invoicing and account reconciliation. Once magstripe point-of-sale terminals were installed everywhere, who would pay the cost of adding chip and PIN terminals? The existing infrastructure hums along nicely—even though merchants are paying for it through card fees, and consumers are paying for it through the higher prices that reflect those passed-on fees. Infrastructural change happens slowly.

But lately, payment systems have become host to tremendous imagination. In our research, we talk to a lot of people trying to develop new payment technology. We hear a lot about the past and the future. One person said American payment systems today feel “a bit like watching Mad Men.” We’ve been told that chip and PIN “smartcards” are “sooo 90s, basically already a relic that will never get traction in the U.S.” that will no-doubt be “leap frogged” by something new even though they work better than magstripe. Industry conferences have names like Money2020, implying a near-ish future that will deliver a radical change to the way we make change. “Physical currency will disappear!”

This is hardly a new promise. In the 1950s, the “cashless society” was as much a part of an idealized modern future as the jetpack and the flying car. Most of today’s dreams of a future without money harken back to a time when money was a commodity in the form of gold or silver—not a government promise. Consider all the new computer-generated “coins”: There are Bitcoins, Dogecoins, Auroracoins and other “alt coins” that make World of Warcraft’s virtual “gold” sound quaint. We hear that the “new gold” will be one new store of value or another: frequent flyer miles, reputation, personal data.

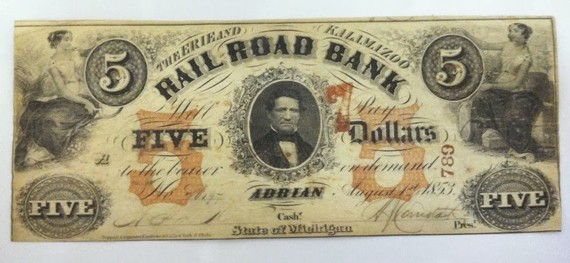

This imagined future turns out to resemble the era of the Jetsons less than it does that of The Lone Ranger (“high ho, Silver!”). In the nineteenth century, money was also open to collective re-imagination. Any number of money and money-like instruments circulated alongside one another: gold dust, foreign coins, real banknotes, fake banknotes, banknotes from defunct banks. As the historian David Henkin points out, a key skill of survival in the new metropolis the ability to evaluate and “read,” even if you were illiterate, all kind of negotiable paper.

This history helps reorient what future money might look like. It might be a future of multiple moneys or money-like things interacting with one another, private currencies challenging the state’s monopoly on money. A chip and pin authenticates identity and opens up access to a remote store of value denominated in state-issued currency. But a future Internet of Things for payments might use tiny wires, sensors and processors to authenticate, track and otherwise interact with plural moneys—loyalty points, private currencies, monetized personal reputation or data. These could also interact with smart shopping carts, allowing for frictionless transactions and speedier shopping excursions. No more waiting in line! (It strikes us that payments visionaries, mostly men, seem to hate spending time shopping.)

We can see glimpses of this future already. The Bitcoins that you might spend in a single day might be kept on your phone in a “hot wallet,” an always-online application to access your Bitcoin, whereas Bitcoins that you can’t afford to lose might be secured in “cold storage” on a computer in a safe, disconnected from the Internet. In another scenario, Apple, PayPal, and a few independent companies are currently developing “beacon” technologies. This hardware broadcasts signals that “wake up” proximate smartphones. When you enter a store, the beacon and your device might transmit “smart value” in form of coupons or money without you or the clerk having to bother with the transaction.

And then there is Coin, the aspiring credit card replacement. It uses an RFID signal to alert you when you leave it behind. And it calls itself a “coin,” evoking the present renewed interest in commodity money. It’s sleek and elegant. It looks, feels and operates exactly like a normal credit card. Indeed, exactly like a normal American magstripe credit card. The latest example of the Internet of Things for money would be exactly as vulnerable to skimming as Bill’s regular old debit card.

Coins, paper, checks, and cards have all shown incredible resistance to being fully replaced. Network effects explain this resilience. With payment technology, everyone has to invest in the change to make it worthwhile. This is what puts the makers of Coin in such a bind: their product would be so much better if it didn’t have to interface with same old magstripe reader, but if it didn’t have to interface with same old mag stripe reader, Americans would probably have chip and PIN in the first place. (Though guess what? Because of the recent Target data breach, chip and PIN may soon be coming to the US.)

So despite all the talk about the return of commodities—non-state currency fanatics’ insistence that cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin are just like digital gold—in fact, neither authority nor natural value underlies new monetary forms. Rather, that power lies in the infrastructure that that makes money move: who manages it, who gets to collect data from it, who decides when and where money can flow through it. Some in the Bitcoin community now realize this, and speak as often of payment protocols as anarchist futures.

Once again, this is nothing new. After the Civil War, monetary policy was a hotly debated. Boston bankers wanted the country to return to the gold standard so that its money could perform on international currency markets. Farmers in Illinois wanted the supply of money to be determined not by gold but by the need for a paper currency as a medium of exchange. The bankers won, for a while. But meanwhile, another battle was being fought over the infrastructure that moved both gold and currency across the nation. The United States Postal Service was struggling to build an infrastructure that could provide universal service to all Americans. The private express industry went everywhere, creating a cartel that fixed prices and exploited workers in the process. Then, when the expresses were finally regulated as common carriers, they consolidated and got into the payment business—money orders and travelers checks—as in the case of American Express.

But unlike the wild west, today the rails, roads, and freight of payment flows have been flattened. A Bitcoin is inseparable from the database of its agents’ transactions since its creation. Indeed, this is the only material form a Bitcoin ever takes! It is one with its network. Similarly, American Express loyalty points are of a piece with the network that carries them. Because of this, Bitcoin and AmEx points have a kind of non-interoperability. They are systems unto themselves that require still other systems—exchanges—in order to work with other payment systems. This points toward a future of closed payment communities linked by new gateways, new toll-takers. In other words, new infrastructures, sitting alongside the old. Coin will depend on magnetic stripe readers and the existing card networks; what will new payments depend on? The same infrastructures, or new ones? Like the old postal service, will there be common carriers for the internet of money-things? Ultimately, this is not just a technical question, but a political one.